Sweden, pt. 4

blue in the face

last one, folks

What horizons of white snow, deserted water and limitless forests are in these blue eyes of a man of the North! What serene boredom in that clear, almost white gaze—the noble and ancient boredom of the modern world, already aware of its death… The wind was blowing through the trees in the park, and I was thinking of the heads of horses hanging from the branches of the Uppsala oaks around the graves of their sovereigns.

—Curzio Malaparte, Kaputt

I.

Like Lou Reed said in the film Blue in the Face, compared to New York City, Sweden is a scary place:

It’s kind of empty. They’re all drunk.

Everything works.

If you stop at a stop light and don’t turn your engine off, people come over and talk to you about it.

You go to the medicine cabinet and open it up and there’ll be a little poster saying IN CASE OF SUICIDE CALL…

You turn on the TV and there’s an ear operation.

These things scare me. New York, no.

Reed is describing the nearly-DDR Swedish 1980s, when the country went right up to the line of becoming a socialist republic and things have changed a lot, but it still kind of hits.

Everything just works. A kind of horror vacuii to an American. But also fascinating and entrancing, a strange miracle. Everything is so highly functional.

Sweden is an outstanding example of an oppressive, ominous setting.

As everyone knows, the country punches above its weight in culture, music, tech and fashion. The country also punches above its weight in pedos and serial killers. True crime and scandi-noir are national obsessions.

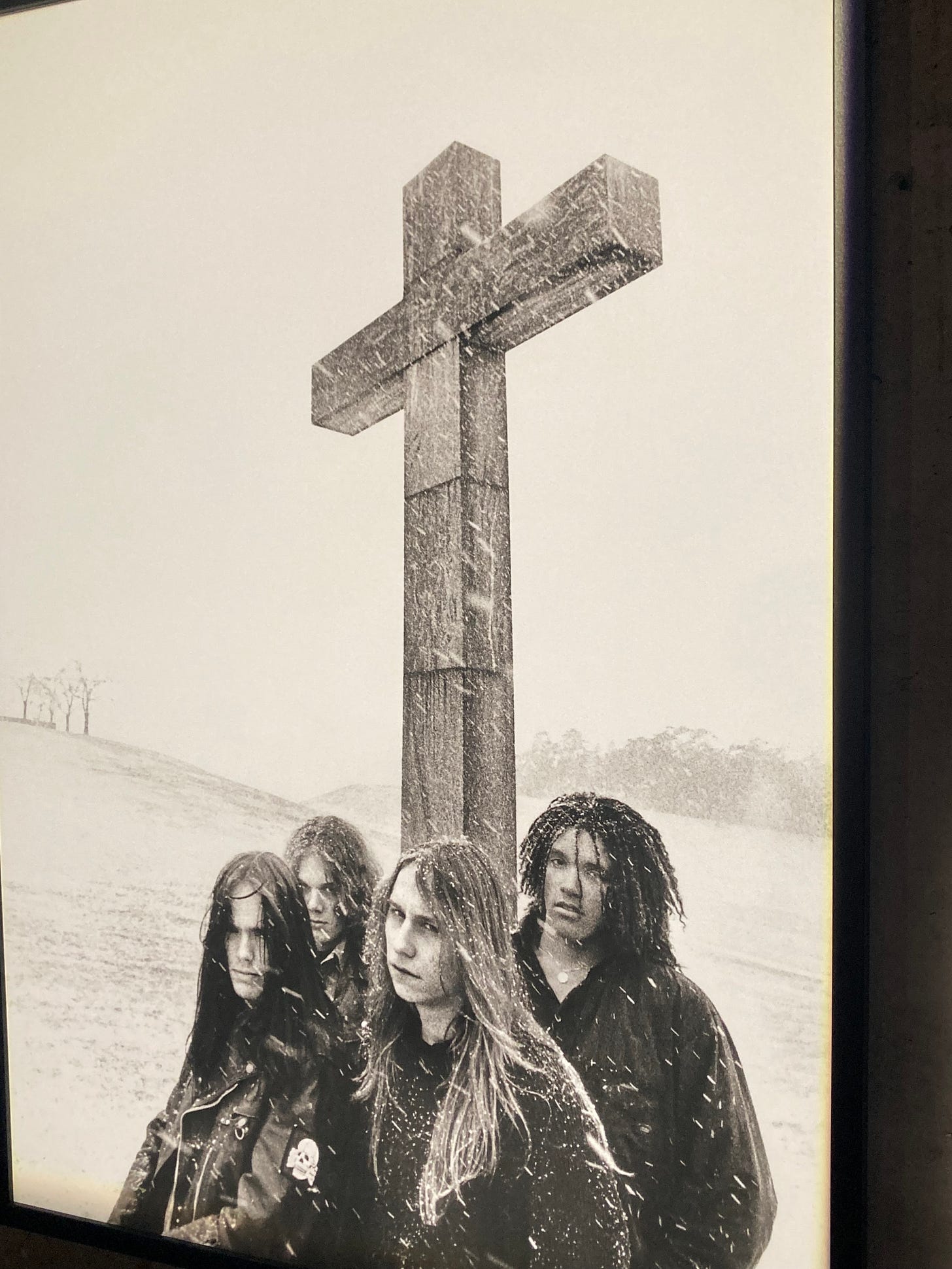

I’m not complaining, honest. I guess I like an ominous setting. I love blackened metal, doom, and crust, music that sounds like guttural growls from hell. I love Lowry’s Under the Volcano set in ominous Mexico, and Bolano’s The Third Reich, set in the very-ominous off-season village of Blanes.

Sometimes when I hear the ice cream man’s jingle-song in the 4 PM dark in the middle of winter, a shiver runs through my heart. What is he doing out there in all that dark and all that cold, trying to sell ice cream? Some poor middle-aged guy from Syria or Iraq, driving around in the rain trying to sell ice cream to little kids in the dark, make his daily bread.

I feel a shiver when it looks like a black metal album outside and the daycare downstairs has brought all the kids out in the yard to play in the sleet and they’re all hooting and hollering and having a great time, Barbaric, I shake my head, olde British imperialist that I am in my soul—leaving children out in the cold to teach them to love the cold and dark... unthinkable.

At our second apartment in Gothenburg, we’d open our balcony door and for hours hear a seriously-paralyzed woman screaming across the courtyard—it sounded like she was being literally murdered. You couldn’t ignore it. It made even the nicest summer days seem evil and sad. It broke the otherwise total silence like a broken mirror.

One day, after a particularly guttural and brutal round of screaming, I got concerned enough to call social services and then the police.

She was fine—it was just her condition. Her caregivers opened the windows or the balcony to give her some air, and we were just hearing her daily nonstop screams.

There’s an older woman with a little Buddhist hat who is always on the street outside our building in Stockholm, she paces back and forth down the big road with her hands clasped behind her back as if she’s doing mindfulness, or she sits on the bench—smiling at everyone with a beatific smile. She looks a lot like Zen author Pema Chodron. I actually looked up Pema Chodron, because for a while I was convinced it WAS Pema Chodron, that she had somehow ended up on my block in her twilight years. Maybe some Swedish zen center. Or married to a Swede. But it wasn’t her.

After a while, after a few nice interactions, I realized she has some kind of dementia. She waves and smiles and says hello to everybody and stares at the street and walks up and down picking up trash and cigarette butts. It’s cold outside, its rainy, it’s snowing and blowing, but I can barely leave the house without her always appearing out of nowhere.

My old buddy Johan, a quintessential Swede, a dad, an academic, a handsome man with nice hair and pretty eyes, once told me that he was afraid of the Swedish forests.

I’m afraid of them too.

Something wrong with them. Something evil. Evil in nature. Like the forests are filled with evil spirits. Even in the summer, the mossy woods have no summer smell, but smell like an old hospital (like the woods in upstate New York). They are kind of delicately beautiful in a way, with the moss and trees and the spongy mossy ground that will swallow you up and is probably filled with Viking Hordes, there are probably swords and helmets and gold all over these terrifying fucking forests, this was a BARBARIAN area…

The way they clean the cold marble stairwells of every apartment complex and it smells like a hospital, the energy-saving light bulbs everywhere clicking on and off, the absolute mania for total societal control and “carbon-neutral” products and renovations.

Every Swedish apartment building has a collective laundry in the basement, and these laundry bureaucracies could have been designed by Adolf Eichmann. There are elaborate, intricate systems for booking, for the amount of time you have in which you can be late to your booking, and once you’re down there, deep in the belly of the building with its energy-saving LED lights, there are seventeen different kinds of machines for washing and straining and drying, and elaborate typed-out rules for cleaning these machines.

The mania for order and structure. And the mania for suffering, for the Lutheran hair-shirt. The things that the Swedes deem to be “luxurious” and “high class” are all uncomfortable—rustic cottages with almost no amenities, scratchy bed sheets and linen clothes that feel like they’re meant for medieval monks, couches and chairs that look fashionable and Danish-designy but are actually stiff and uncomfortable to sit on, the way they take their families bicycling and skiing in the rain and wind and snow.

In America, our idea of luxury is a life of no resistance—Lyfts, giant, deep soft modular couches so big you could spread out and sleep in them, silk sheets and plush bathrobes and endless delivery food.

I’m not complaining, I swear, but over time I’ve seen that these approaches to life couldn’t be more different. One says life is duty, hard-work, suffering, and the other says find a good hustle, be a good little middle-man, and life can be nonstop pleasure. Is there nothing in-between?

II.

Since coming to Sweden, I have often found myself in the position of calling an ambulance for strangers.

Someone’s always bleeding on the ground, a junkie is turning blue outside of Old Corner, his junkie girlfriend is trying to carry him away, screaming at the tattooed paramedics; an old lady with a walker hit her head on the icy sidewalk and the blood is pooling in the snow; oh god, now a very-pregnant Somali woman has fallen at the commuter station, and pedestrians just walk on by. I stop and stay with her and pick her up and a few others stop. Fellow immigrants stop to pick up fellow immigrants, good middle-class Swedes stop and pick up good middle-class Swedes, the rest just walk by and stare their Swedish stare, the stare of a thousand gray lakes and endless forests.

The ambulances don’t rush, they take their sweet time.

III.

I have two bars I like to go to, and I like to go to them alone—to stare out the window, read my impenetrable history books, text faraway friends, and obsessively edit and re-edit long pieces of writing, thinking I’m making them better when I’m actually making them worse.

Both are wood-paneled dives, run by Arabs. All the best dives in Sweden are all run by Arabs—Kurds, Assyrians, Iraqis, Syrians.

Both play transcendent playlists of American pop hits and monster ballads from the 80s and 90s, not the mega-hits, but the kinds of songs you know but have forgotten about and that you all of a sudden remember that you love once you hear them, and it opens up a crazy wormhole in memory as you try to remember where you know the song from; combined with the two beers and the wistfulness of being so far from home and so far from the past, it’s enough to nearly bring me to tears. I Shazam the songs and save them in a playlist and walk around listening to them and singing them for days after, or I go try them out at karaoke, as if trying to recapture some fuzzy memory that half-arises and then dissolves. (As I sit here editing this, The Sounds “We’re Not Living in America” has just come on. The lyrics are: We’re not living in America / but we’re not sorry)

The bar in Stockholm is tucked in the Park Slope part of town behind the subway station, a vestige of the neighborhood’s grittier past—it’s called Pub Diset, “The Fog.”

I love that name for a bar, The Fog.

There are two words for Fog in Swedish. Because fog is a fact of life. Diset and dimma. It has been explained to me that Diset is a soupy fog.

The main clientele is pensioners and Arab and African guys nursing beers and watching football, old worn-out alcoholics playing video poker in the corner, and a light frosting of groups of Swedish hipsters.

At Diset, I always meet interesting people—Kurds and ex-PKK dudes and queer and trans Indonesians and goth artists and forlorn African dudes and happy Jamaican dudes.

Sometimes I see The Middle-Aged American there. He’s watching football on the tiny TV. He looks a lot like Chris Hedges. I get the feeling he is some kind of “Sweden correspondent” for The Guardian. I avoid him because his steely cold eyes behind his spectacles scare me, and because I’m afraid of becoming him, another soul in purgatory. I talked to him one time and, smiling smugly, he said he had a kid with a Swedish woman and that was why he was in Stockholm, he was trapped. Happily trapped. Shipwrecked.

This situation is so common that these people form their own category of immigration—the “love refugees.” Usually they’re men, very often British or Irish, sometimes American. But women too, Spanish or American, who got lured to these shores by the Sirens and ended up staying.

They are not fleeing war and poverty. They just met a great Swede—someone so much different than the people back home—and leave America or England or wherever behind to join them here.

Usually within two to four years, the “love refugees” will have a kid with the Swede—then slowly they will realize their cultural differences and incompatibility—and split soon after and stay to co-parent. But they’re often sort of ok with that. For some this is a dream, and anyway there are far worse fates.

This is what happened to me, minus the kid.

Too alienated to go back home, but too stubborn to fully integrate, I guess it’s a kind of purgatory, but a pleasant one.

If Stockholm is DC or New York, with its snobbiness and middle-class careerism and cultural cache, Sweden’s second city, three hours by train across the country on the West Coast called Gothenburg, is more like Seattle or Baltimore. A gritty port city. A militant left wing working class history. There is a friendly, swashbuckling light kind of gentrification. Artists, crust punks, underemployed literati, noise musicians—all of them can still pay the equivalent of 500 bucks a month for a studio or one bedroom in an OK part of town.

The other bar I love is called Old Corner. It’s a kind of roadhouse on the edge of town. The neighborhood is a kind of rapidly-gentrifying Venn diagram of left-wing punks and activists punks and immigrants, and young families who buy there for the low cost of living.

I loved to take the five-minute walk from our apartment in the softly falling snow and step into warm, humid Mos Eisley Cantina, filled with all the scum and villainy of the universe. At one point in time I loved Old Corner so much that I spent more time there than at home—writing, reading, talking to people.

Like Rick’s—Rick’s in Casablanca—That’s what the Swedish sunk bars remind me of.

The owner of Old Corner even has a Humphrey Bogart look—smiling, in charge, at the peak of his game. Late at night it gets rowdy and they stop selling full pizzas and start selling slices of pizza, two bucks a slice.

Maybe they’ll be a fistfight. I hope there’ll be a fight. Maybe I’ll have a conversation with a bald-headed nazi guy and change tables when I get bored of his bullshit, or the crusty bartender will tell me about his health problems.

IV.

Sometimes I have a dream and in the dream I see a place I have never seen before and I do not know where it is, but I know it’s the place I will spend the rest of my life. Its surrounded by high dunes, like mountains in front of the ocean, and there is a little sleepy, sandy road with a couple of small shops on it. The people are friendly and the sun hits the sand and shops and it is a gentle kind of morning sun. It is not exactly a surfing town, it is not in Latin America, but it’s not not a surfing town—maybe it’s hidden somewhere in the mouth of the South?—I do not know, but I know it’s sheltered away down a very small sandy backroad.

When I wake up I feel a sense of peace and fate that I have not felt for a long time, maybe ever. I close my eyes wishing to be transported back, but it’s gone, the sunshine burning away as the black anxious mud of the world reasserts itself. What a cool little town, I think I’d like to stay there…

My sad little broken American, are you pained by how your country has taught you to push forward like those self-flagellating penitents, that if you don’t push and work and socialize and smile and extend your circle you will fall off and die? Do the cold eyes and laughs and prepared statements of productivity and well-conceived irony and staying late at the office every night until you die trouble you? Are you pained by your country’s demand that you have relentless suffocating optimism and wily scheming? Do you hate how you look into the eyes of an American friend and you can’t tell what’s there, behind the big white American smile and words you have no idea what they’re actually thinking? How you can’t bear your pains to people because our society believes pain and weakness and turmoil of the soul makes them like lepers, and they instinctive recoil, as if exposure might be contagious?

Do you constantly notice how, in our GREAT country, all eyes turn towards an INDIVIDUAL? For all the talk of equality and collective effort, it’s a social circus with values that lionize individuals, all eyes look longingly toward “the leader” the most individualist… the ridiculous, cultivated individual identities, that draw attention to themselves with the loudest voices or charisma or extreme looks, they talk loud, and express themselves constantly…does it disgust you little man?

Do you wince when you see people trying to “stand out from the crowd” by dancing, or acting out, or shouting, or doing backflips into the pool when everyone else is jumping in, or their strange clothing, or their extreme, puritanical views?

Individuality overrated, the grand social circus, and Americans are so gullible for it—all someone has to do is “stand out” and a crowd gathers around to admire them for expressing themselves, no one ever questions the narcissism of this behavior… the absence in someone that causes one to want to be a unique individual rather than engage in collective effort, not cultivate themselves as a personality, not lengthen their shadow, but just fade in with the rest…

Does it disgust you when people try to stand out in this way? Perhaps Norrland is for you….where the vestiges of the Law of Jante still hold sway, an old law that says “don’t think you’re anyone special. Don’t act special. Don’t try to stand out.”

Sometimes I think about the rivers and creeks and nature of my native Southern lands and my family, and I want to go home. Sometimes I badly want to go home, to be done once and for all with this strange place. I can go home, of course. But home isn’t really home anymore, it’s changed too much or I’ve changed too much, or maybe those are just things I’ve told myself that aren’t true.

One day, maybe, I will open a little bar in some forsaken lilac-dark corner of the South and call it The Fog. One day, if I ever truly return home, if I don’t die and get buried in their sodden, treeless rain-soaked graveyards here, I’ll put up a red neon sign up on scaffold over the front door, an eternal bat-signal for the broken, the lonely, the forsaken.

I know there are better places, warmer places, more familiar places, but I stay here. I don’t know why. I can’t even put my finger on it—so I stay. It’s warm inside at Rick’s, so I stay in Casablanca.

The mossy ground imagery captures something essential about how oppressive functionality can feel. Swedish efficiency and American hyperindividualism are both exhausting in opposite ways - one demands you disappear into collective order, the other that you constantly perform uniqueness. Your description of those hospital-smelling forests and the basement laundry bureaucracies designed by Eichmann gets at why "everything works" can be its own kind of horror vacuii.

Thanks wonderffully writen and quite true on both Sweden and the hyperindivudalism in the US. My own take is in the winter you have to be south of the Alps best near the European bathtub.